Miniatures lie

in my cupboard

Like pawns

on invisible,

black and white squares;

staring at me

When I look at them

they evade my eyes

One of them

with a picture of gypsy girl

steals glances at me

Can she hear

the rhubarb of my heart?

What is it really?

A liturgy

or have I been hexed?

In a dark recess

of my heart

I caress the gypsy girl

She puts up

a mock fight with me;

snatching cherries

from the clutches of my lips

Someone knocks on the door

The spell breaks

The gypsy girl is nothing

but a label on a tiny bottle

But I can still smell

the gypsy girl's musk

My shirt is stained

A cherry

has squirted on it

Friday, April 28, 2006

Wednesday, April 26, 2006

The Missing Man

A week after his disappearance, Srikant’s family received an envelope. His father Bhagirath, responding to a knock on the door, collected it from a postman, whose nose was like an eagle’s beak.

Srikant’s name, with his address beneath, was typed neatly on the envelope and on the other side the sender’s name read as: The Marketing Manager, The Times of India. Bhagirath tore it from one corner, with the help of his silver paper cutter, lying on a table. It was a gift in lieu of annual subscription of a weekly magazine. Inside the envelope, Bhagirath found a note and a newspaper cutting. He read the note first.

Dear Mr. Srikant

Kindly find attached a cutting of the advertisement booked by you under the ‘Missing Persons’ column of The Times of India. Your ad appeared in the Delhi and Mumbai edition of the newspaper on March 22. In case of any error in the ad, please contact the Marketing Manager.

Bhagirath looked at the cutting. There was a photograph of a woman, quite clear, despite the cheap newspaper print. The woman smiled in the photograph. She wore a sleeveless T-shirt and trousers and looked very happy posing for this picture. There were details given below. Sneha, aged 34, fair complexion, tall. A small cut on her left arm. Missing from her residence since two months. In case of any information, please contact immediately: Srikant. There was Srikant’s e-mail and his mobile number provided along with his name. The same mobile number which went off that night. The night, when Srikant did not come back home.

Bhagirath felt his head spinning. He caught hold of a corner of the table and sat on the chair, as his legs wobbled. He had no clue about this woman. And he did not know how Srikant knew her and why he had given an ad in the newspaper. And where had he disappeared himself?

That night, the family waited for Srikant’s arrival. If he got late beyond 9 pm, he would always call and inform his father. Or his wife Kavita. Otherwise, they would always have dinner together by 9.30 pm. But that night, when Kavita tried to reach her husband on his mobile, she could not reach him. It was switched off.

By midnight, they were quite worried. Had he met with an accident? They tried calling few friends, with whom he usually spent his evenings. Nobody seemed to have any clue about his whereabouts.

Bhagirath handed over the newspaper cutting to Kavita. ‘Do you know this woman?’ She held it with trembling hands. She looked at it and then read the note. She did not know her. She had never heard her name. She had never seen her.

When he did not come back till the next evening, Bhagirath went to the Police. An hour after he had returned from the Police Station, a Sub-Inspector and a constable came to their house. They wanted to go through Srikant’s belongings. Bhagirath gave a nod.

‘Your son was very fond of books,’ the Police officer said as he looked at the huge rack of books in Srikant’s bedroom. Bhagirath did not know whether the officer was telling him or asking him. He kept silent.

After taking few more pictures of Srikant, they left. Kavita found a book which Srikant was reading the night before he went missing. It lay on his table, over a sheaf of papers. He had drawn some sketches here and there and scribbled in his usual indecipherable writing. The book was a novel by Herman Hesse. Narcissus and Goldmund. She opened it. On one page, Srikant had highlighted a passage from the novel with a fluorescent green highlighter:

A man’s wishes may not always determine his destiny, his mission; perhaps there are other, predetermining, factors.

Srikant’s name, with his address beneath, was typed neatly on the envelope and on the other side the sender’s name read as: The Marketing Manager, The Times of India. Bhagirath tore it from one corner, with the help of his silver paper cutter, lying on a table. It was a gift in lieu of annual subscription of a weekly magazine. Inside the envelope, Bhagirath found a note and a newspaper cutting. He read the note first.

Dear Mr. Srikant

Kindly find attached a cutting of the advertisement booked by you under the ‘Missing Persons’ column of The Times of India. Your ad appeared in the Delhi and Mumbai edition of the newspaper on March 22. In case of any error in the ad, please contact the Marketing Manager.

Bhagirath looked at the cutting. There was a photograph of a woman, quite clear, despite the cheap newspaper print. The woman smiled in the photograph. She wore a sleeveless T-shirt and trousers and looked very happy posing for this picture. There were details given below. Sneha, aged 34, fair complexion, tall. A small cut on her left arm. Missing from her residence since two months. In case of any information, please contact immediately: Srikant. There was Srikant’s e-mail and his mobile number provided along with his name. The same mobile number which went off that night. The night, when Srikant did not come back home.

Bhagirath felt his head spinning. He caught hold of a corner of the table and sat on the chair, as his legs wobbled. He had no clue about this woman. And he did not know how Srikant knew her and why he had given an ad in the newspaper. And where had he disappeared himself?

That night, the family waited for Srikant’s arrival. If he got late beyond 9 pm, he would always call and inform his father. Or his wife Kavita. Otherwise, they would always have dinner together by 9.30 pm. But that night, when Kavita tried to reach her husband on his mobile, she could not reach him. It was switched off.

By midnight, they were quite worried. Had he met with an accident? They tried calling few friends, with whom he usually spent his evenings. Nobody seemed to have any clue about his whereabouts.

Bhagirath handed over the newspaper cutting to Kavita. ‘Do you know this woman?’ She held it with trembling hands. She looked at it and then read the note. She did not know her. She had never heard her name. She had never seen her.

When he did not come back till the next evening, Bhagirath went to the Police. An hour after he had returned from the Police Station, a Sub-Inspector and a constable came to their house. They wanted to go through Srikant’s belongings. Bhagirath gave a nod.

‘Your son was very fond of books,’ the Police officer said as he looked at the huge rack of books in Srikant’s bedroom. Bhagirath did not know whether the officer was telling him or asking him. He kept silent.

After taking few more pictures of Srikant, they left. Kavita found a book which Srikant was reading the night before he went missing. It lay on his table, over a sheaf of papers. He had drawn some sketches here and there and scribbled in his usual indecipherable writing. The book was a novel by Herman Hesse. Narcissus and Goldmund. She opened it. On one page, Srikant had highlighted a passage from the novel with a fluorescent green highlighter:

A man’s wishes may not always determine his destiny, his mission; perhaps there are other, predetermining, factors.

Sunday, April 23, 2006

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

Saturday, April 15, 2006

Then and Now

Of Horses and Illustrations

I have been reading a number of Graphic novels these days. Sharad had got Art Spiegelman's Maus from Manchester. H sent the complete volume of Joe Sacco's Palestine. Last night, I told Sharad that I need to tell a number of stories. Mostly from Kashmir. For my stories, I don't have to depend on 'Saande ka tael' (If you know what I mean).

B said rightly, few weeks back, that if he spends an hour with his village barber, he comes back with a sackful of stories. And his barber is so witty, B tells me. One example of his humour: B sahab, you know there are only two creatures who have benefitted from terrorism in Kashmir - one the horses and two impish children. Horses because there are hardly any tourists now and they no longer have to carry fat Marwari families on their backs. Children because they are no longer required to attend school.

Meanwhile, I am trying to improve my drawing skills. Do you think I stand a chance?

Saturday, March 25, 2006

A Journey from Kashmir to London

A dog-eared copy of Crime and Punishment changed his life. My friend Basharat Peer from Tehelka told me the story of Iqbal Ahmed, who left Kashmir in 1993 to work in London. He was 26. Iqbal worked at a number of places and is currently a porter in a London hotel. It was in Kashmir that he got hold of the classic book and decided to become a writer. His loneliness as an immigrant and the way London failed him inspired him to write a book titled: Sorrows of the Moon, A Journey Through London.

You can read his experiences he shared with the London Review of Books here.

You can read his experiences he shared with the London Review of Books here.

Only one Dream

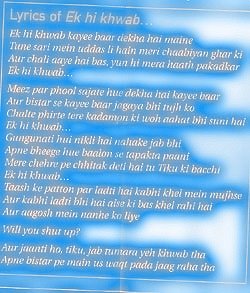

This is a box item from Page number 113 of Fimlmfare, May 2005 issue. I was flipping through this magazine to pass time as my Hair Dresser Pran drank tea. And then suddenly this page flashed in front of me. As Pran got busy with cutting someone's hair, I silently tore away this page. I could not resist because for long I had been wanting to lay my hands upon these lyrics. These have been penned by Gulzar for film Kinara.

Gulzar says he always wanted to write songs that could be part of narrative. Ek hi khwab... was one such experiment. Gulzar remembers taking this song to Pancham (RD Burman). When he came to learn that Gulzar wanted him to put these words to music, he smacked his head and exclaimed: Koi kaam seedha nahi karta hai.

This song was recorded in Bhupinder's and Hema Malini's voices. Bhupi was given a pair of headphones and asked to strum his guitar spontaneously. Bhupi did it in one take.

Thursday, March 23, 2006

You have come, what for?

Life comes a full circle

I wait for it

To come to me

After taking

A merry-go-round

I have a gift for Life

A watermelon

Packed in a condom

I will hand over

The gift, to Life

And wink my eye

Saying: Chattri se Azaadi.

I wait for it

To come to me

After taking

A merry-go-round

I have a gift for Life

A watermelon

Packed in a condom

I will hand over

The gift, to Life

And wink my eye

Saying: Chattri se Azaadi.

Wednesday, March 22, 2006

The Design of Madness

He was mad. His madness did not require him to wear torn clothes and let saliva drip from the corners of his mouth. Or to mumble to himself. Or to throw stones at people. His madness had its own way. Its own design.

Like this. He drank whisky with roasted grams. Sometimes he would begin drinking at three in the morning. Switch on his CD player and listen to the melancholic songs of Talat Mehmood. And cry very silently as the night broke down into sunrise. And then he would wet his hair, look into the depths of his retinas in the mirror and laugh. Laugh till he collapsed.

Sometimes he would begin writing in the evening. He had held himself for long. No longer anymore. He would put choicest Bhangra tunes on his player. After pouring himself half-a-finger whisky, he would begin typing. And then rise suddenly from his seat and begin dancing. His dance was so intense that frenzy would hide itself. When one song finished, it meant five hundred words and innumerable tiny droplets of sweat on his forehead. And then another half-a-finger, another song and another five hundred words. And a round sun of sweat on his shirt.

Aaja mere khaetan di bahaar ban aaja

Faslan da roop da shingaar ban aaja

Come on, be the spring of my fields

Come, be the ornament of my harvest

That was Amarjit Sandhu doing a private show for him. He danced with his eyes closed. He would even type with his eyes closed. And blindly take a swig from his glass. When he was exhausted, he stood in front of the mirror again. Looking intensly at himself, as if the mirror enabled him to see the blood surging in his arteries, he would laugh again.

By that time, Maya would appear. He would kiss her delicately, undress her and enter her. While he made love, he would recite poetry. Mostly James Thomson.

And so throughout the twilight hour

That vaguely murmurous hush and rest

There brooded; and beneath its power

Life throbbing held its throbs supprest:

Until the thin-voiced mirror sighed,

I am all blurred with dust and damp,

So long ago the clear day died,

So long has gleamed nor fire nor lamp.

Maya would begin to ebb away from his febrile consciousness. She was an illusion after all. But his madness was real. The words that you read right now are a testimonial.

Like this. He drank whisky with roasted grams. Sometimes he would begin drinking at three in the morning. Switch on his CD player and listen to the melancholic songs of Talat Mehmood. And cry very silently as the night broke down into sunrise. And then he would wet his hair, look into the depths of his retinas in the mirror and laugh. Laugh till he collapsed.

Sometimes he would begin writing in the evening. He had held himself for long. No longer anymore. He would put choicest Bhangra tunes on his player. After pouring himself half-a-finger whisky, he would begin typing. And then rise suddenly from his seat and begin dancing. His dance was so intense that frenzy would hide itself. When one song finished, it meant five hundred words and innumerable tiny droplets of sweat on his forehead. And then another half-a-finger, another song and another five hundred words. And a round sun of sweat on his shirt.

Aaja mere khaetan di bahaar ban aaja

Faslan da roop da shingaar ban aaja

Come on, be the spring of my fields

Come, be the ornament of my harvest

That was Amarjit Sandhu doing a private show for him. He danced with his eyes closed. He would even type with his eyes closed. And blindly take a swig from his glass. When he was exhausted, he stood in front of the mirror again. Looking intensly at himself, as if the mirror enabled him to see the blood surging in his arteries, he would laugh again.

By that time, Maya would appear. He would kiss her delicately, undress her and enter her. While he made love, he would recite poetry. Mostly James Thomson.

And so throughout the twilight hour

That vaguely murmurous hush and rest

There brooded; and beneath its power

Life throbbing held its throbs supprest:

Until the thin-voiced mirror sighed,

I am all blurred with dust and damp,

So long ago the clear day died,

So long has gleamed nor fire nor lamp.

Maya would begin to ebb away from his febrile consciousness. She was an illusion after all. But his madness was real. The words that you read right now are a testimonial.

Monday, February 20, 2006

The Life of Pandey Ji

The Bus Stop is no longer there. And neither is the huge billboard behind it. The flyover has devoured them. Delhi is experiencing modernisation. Everything needs to shine. With spit and polish of ambition. There is no time to value emotions. Or to preserve monuments of despair. Of hopelessness. Like the one, you could see near the Okhla vegetable market. On the yellow signboard of that Bus Stop. Before the flyover came up. Read More...

Second Part: Life is a Diode

Second Part: Life is a Diode

Sunday, February 12, 2006

Sunday, February 05, 2006

Campaign In Rajasthan

I have just returned back from Rajasthan, where we ran a campaign for Girl Child rights in Barmer district. The campaign also included a Bike rally from Barmer to Jodhpur, which passed through almost hundred villages. For more about this campaign log on to www.halfworld.blogspot.com

Pics (From top to bottom)

1. With friend Sharad Sharma of World Comics India outside Jodhpur railway station.

2. Examining my bike near Kavas village.

3. The rally has reached Baitu village.

4. Motorcycle rally reaches Pachpadra village famous for its salt lakes.

5. With International Bike racer Bittoo Sondhi.

6. Running along with cameraperson Tara Joshi to get a better shot of the rally.

7. Recording a song in Haathma village.

Pics (From top to bottom)

1. With friend Sharad Sharma of World Comics India outside Jodhpur railway station.

2. Examining my bike near Kavas village.

3. The rally has reached Baitu village.

4. Motorcycle rally reaches Pachpadra village famous for its salt lakes.

5. With International Bike racer Bittoo Sondhi.

6. Running along with cameraperson Tara Joshi to get a better shot of the rally.

7. Recording a song in Haathma village.

Thursday, January 19, 2006

The Elbow Cream

Today, I write about you

Words come from my gall bladder

All drenched in bile,

And wine made from cider

I remember those summer afternoons

When coal tar would stick on shoes

And you would dress up in cotton Pyjamas

Planning to set up a ruse

You, lost in your own world

And partially in mine

You’d seek refuge in the recycled paper

And lie down beside me

On the top floor of that house

I would go to sleep

and you would look at me

And then lie down beside me

(as I felt the mole near your navel)

Remember? You were after me those days

Trying to change the destiny of my elbows

Armed with, do you remember, the elbow-cream?

You’d be soon leaving for Kolkata

I knew you had surrendered

Their happiness mattered to you.

But what about my elbows, Nina?

Words come from my gall bladder

All drenched in bile,

And wine made from cider

I remember those summer afternoons

When coal tar would stick on shoes

And you would dress up in cotton Pyjamas

Planning to set up a ruse

You, lost in your own world

And partially in mine

You’d seek refuge in the recycled paper

And lie down beside me

On the top floor of that house

I would go to sleep

and you would look at me

And then lie down beside me

(as I felt the mole near your navel)

Remember? You were after me those days

Trying to change the destiny of my elbows

Armed with, do you remember, the elbow-cream?

You’d be soon leaving for Kolkata

I knew you had surrendered

Their happiness mattered to you.

But what about my elbows, Nina?

Monday, January 16, 2006

Mind wanders in Meerut

He wore a silk scarf. One last time, he thought. He also held a silken handkerchief in his hand. Ram Bahadur put his sleeping bag and his suitcase in the rear of the car. As he shut the dickey, two crows sitting on the electric pole became alert. They tried to ward off their fear, hopping restlessly on their feet, but then decided to fly away. Ram Bahadur looked at him meaningfully and he gave a nod. The time had come...

Saturday, January 14, 2006

Postman, Bouncing High

A paralysis has gripped me. There is internal bleeding as well. Of words, which don’t come out. I imagine myself, on a bed in a hospital, wrapped in a calm, white sheet. A needle lies embedded in one of my veins, near the elbow joint. I also visualise a red-coloured Thesaurus attached to it, hanging upside down on the drip stand. I imagine.

I think of myself to be a Postman at a hill station. I walk on the lonely stretches, negotiating bends and curves; a bunch of envelopes in my hands and an old-fashioned black umbrella held under my left arm. I stop at the tea shop. I have a bun and an extremely sweet tea, served in a chipped glass. Sometimes sun shines. Sometimes I cut through the mist. And sometimes I have to open the umbrella.

Actually it is nothing but loneliness. Also, there is no agitation of mind. My inner demons are in a state of comatose. I am stuck. Struck off too; struck off from my own margins.

I try to write. Like:

When he saw a snake creeping over his leg; making a rustling sound on his silken pyjamas, he knew the time had come. Time to tell the story. (Sentence left as it is)

Insalubrious. (Nothing)

It rained heavily as we carried his body till the main road. The load was very heavy, almost backbreaking, despite the fact that he was a mere skeleton now. But carrying him from his cottage till the main road, climbing those fifty-eight steps, laden with bare leaves, we stopped at various places and tried to take stock of our breaths – the phenomenon that he had ceased to perform. (Harmonica, four years ago; as I saw it. MS word file closed)

Maqbool Sherwani. Hindu astrologer; the story of 300 apple cases. Snake bite outside Bhadrakali temple. Raahchok, the ghost. She jumped into the river. Dost Mohammed jumped after her. Leather sandals for seventeen rupees. It was snowing when I opened my eyes. Six months had passed. (Wrote it on the stick pad and pasted it on the CPU)

Yes, aware that I am dying,

I carry my body on my back

Into my mind. Take a shovel

Dig myself a pit. It’s simple. (Doc’s poem. Put it back in the cupboard)

Isko kisi ki arzoo bhi nahi. This does not desire of anything. This. This. Write Rahul write. For God sake write. Please. Write for the sake of that red wall. Write for the sake of that look in your eyes (Secret). Write for the sake of that thought in your mind (Top Secret).

If I can bounce high. High-bouncing self, I must have you!

I think of myself to be a Postman at a hill station. I walk on the lonely stretches, negotiating bends and curves; a bunch of envelopes in my hands and an old-fashioned black umbrella held under my left arm. I stop at the tea shop. I have a bun and an extremely sweet tea, served in a chipped glass. Sometimes sun shines. Sometimes I cut through the mist. And sometimes I have to open the umbrella.

Actually it is nothing but loneliness. Also, there is no agitation of mind. My inner demons are in a state of comatose. I am stuck. Struck off too; struck off from my own margins.

I try to write. Like:

When he saw a snake creeping over his leg; making a rustling sound on his silken pyjamas, he knew the time had come. Time to tell the story. (Sentence left as it is)

Insalubrious. (Nothing)

It rained heavily as we carried his body till the main road. The load was very heavy, almost backbreaking, despite the fact that he was a mere skeleton now. But carrying him from his cottage till the main road, climbing those fifty-eight steps, laden with bare leaves, we stopped at various places and tried to take stock of our breaths – the phenomenon that he had ceased to perform. (Harmonica, four years ago; as I saw it. MS word file closed)

Maqbool Sherwani. Hindu astrologer; the story of 300 apple cases. Snake bite outside Bhadrakali temple. Raahchok, the ghost. She jumped into the river. Dost Mohammed jumped after her. Leather sandals for seventeen rupees. It was snowing when I opened my eyes. Six months had passed. (Wrote it on the stick pad and pasted it on the CPU)

Yes, aware that I am dying,

I carry my body on my back

Into my mind. Take a shovel

Dig myself a pit. It’s simple. (Doc’s poem. Put it back in the cupboard)

Isko kisi ki arzoo bhi nahi. This does not desire of anything. This. This. Write Rahul write. For God sake write. Please. Write for the sake of that red wall. Write for the sake of that look in your eyes (Secret). Write for the sake of that thought in your mind (Top Secret).

If I can bounce high. High-bouncing self, I must have you!

Wednesday, January 04, 2006

Friday, December 30, 2005

This Characterless String

Bazaar mein,

baune khambe ke upar

Teen baar mudi hui

eik charitraheen rassi

Koi khambe ko chhue

to fanfukaarti hai,

Naagin si bal khaati hui

eik charitraheen rassi

Do premiyon ko dekhkar

thoda hilti hai

maano laaj se ho simti hui

eik charitraheen rassi

Aur saamne madiralay mein

shaam guzaarti hai wo

dekho, jhumkar nikalti hui

eik charitraheen rassi

Hai to wo khaane peene ke thelon ke beech,

pur unse duur uska apna chulha hai

alag khichdi pakati hui

eik charitraheen rassi

A translation by my friend Tanzan Senzaki:

This characterless string

Is clinging to a stumped pole,

Going around it three times,

In the vendors’ street.

Many lovers she has.

But this one,

This pole is special,

For the characterless string.

Should someone touch the pole,

She uncoils fast like a snake

And snaps back sharply at him.

This characterless string.

When she sees two lovers together,

She acts as if drenched in shame.

This characterless string.

She spends her evenings at the pub.

Look there she is,

Walking out all drunk.

This characterless string.

Though in the middle of vendors’ street,

She cooks her hotchpotch in a pot,

Placed in a hearth away from street.

This characterless string.

baune khambe ke upar

Teen baar mudi hui

eik charitraheen rassi

Koi khambe ko chhue

to fanfukaarti hai,

Naagin si bal khaati hui

eik charitraheen rassi

Do premiyon ko dekhkar

thoda hilti hai

maano laaj se ho simti hui

eik charitraheen rassi

Aur saamne madiralay mein

shaam guzaarti hai wo

dekho, jhumkar nikalti hui

eik charitraheen rassi

Hai to wo khaane peene ke thelon ke beech,

pur unse duur uska apna chulha hai

alag khichdi pakati hui

eik charitraheen rassi

A translation by my friend Tanzan Senzaki:

This characterless string

Is clinging to a stumped pole,

Going around it three times,

In the vendors’ street.

Many lovers she has.

But this one,

This pole is special,

For the characterless string.

Should someone touch the pole,

She uncoils fast like a snake

And snaps back sharply at him.

This characterless string.

When she sees two lovers together,

She acts as if drenched in shame.

This characterless string.

She spends her evenings at the pub.

Look there she is,

Walking out all drunk.

This characterless string.

Though in the middle of vendors’ street,

She cooks her hotchpotch in a pot,

Placed in a hearth away from street.

This characterless string.

Of Human Bondage

It was not true that he would never see her again. It was not true simply because it was impossible.

Somerset Maugham, Of Human Bondage

Writing a line or two on every page. Page after page. Then making paper boats out of them. And then turn on the kitchen sink...

Somerset Maugham, Of Human Bondage

Writing a line or two on every page. Page after page. Then making paper boats out of them. And then turn on the kitchen sink...

Wednesday, December 28, 2005

A Poem in Hindi

A co-traveller on the Intentblog, Tanzan Senzaki has translated my Hindi poem in free English verse: (You can find the original - in Roman - below this translation)

Time does not hang

On trees for me,

It passes like a rope passes

Through a bull’s nose

Even if I am still

It still moves on

Marching past my pulse

Carrying my subconscious

In a sack on its back,

To savor the sweetness of future

It still passes on

Once I ran fast after it,

Asking it to stop and stay

Under the tree of my memories

Blinking its eyes it marched ahead,

Saying if it did stop,

My pen too would stop,

And only when it moved

‘Now’ became ‘yesterday’

Making my memories thunder in the skies

And passing them on into my pen

Time moved on

I turned back

Reaching far back,

I heard the skies thunder

And my pen moved on

Translated from my Hindi Poem:

Mujhe Samay, Paed pur latka hua nahi milta

Wo guzarta hai -

guzarta hai, jaise bael ke nathunon se nakael

Uske saamne mein thithak bhi javun, pur wo

meri nabz pur kadam taal karte hue

aage nikal padta hai

Apni peeth pur mere antarmann ka pitthu baandhe

wo bavishya ka gud khaane daud padta hai

Maine use raukne ke liye eik baar daud lagayi

aur poocha - ki wo aaram kare

meri smritiyon ke vraksh ke neeche

Wo palke jhapkaata hua mujhe dekhta gaya

lekin ruka nahi

aur phir wo muskuraya

bola -

mein agar ruk gaya to tumhari kalam ruk jaayegi

kyunki mein jab chalta hun

to hi 'ab' kal banta hai

jiske aasman mein smritiyan

bijli bankar kaundh ti hein

aur tumahri kalam ki syaahi mai tabdeel ho jaati hai

Wo chalta gaya

aur mein bhi mudkar chalne laga

duur nikal aaya

aur phir bijli kaundh ne lagi

aur meri kalam chalne...

Time does not hang

On trees for me,

It passes like a rope passes

Through a bull’s nose

Even if I am still

It still moves on

Marching past my pulse

Carrying my subconscious

In a sack on its back,

To savor the sweetness of future

It still passes on

Once I ran fast after it,

Asking it to stop and stay

Under the tree of my memories

Blinking its eyes it marched ahead,

Saying if it did stop,

My pen too would stop,

And only when it moved

‘Now’ became ‘yesterday’

Making my memories thunder in the skies

And passing them on into my pen

Time moved on

I turned back

Reaching far back,

I heard the skies thunder

And my pen moved on

Translated from my Hindi Poem:

Mujhe Samay, Paed pur latka hua nahi milta

Wo guzarta hai -

guzarta hai, jaise bael ke nathunon se nakael

Uske saamne mein thithak bhi javun, pur wo

meri nabz pur kadam taal karte hue

aage nikal padta hai

Apni peeth pur mere antarmann ka pitthu baandhe

wo bavishya ka gud khaane daud padta hai

Maine use raukne ke liye eik baar daud lagayi

aur poocha - ki wo aaram kare

meri smritiyon ke vraksh ke neeche

Wo palke jhapkaata hua mujhe dekhta gaya

lekin ruka nahi

aur phir wo muskuraya

bola -

mein agar ruk gaya to tumhari kalam ruk jaayegi

kyunki mein jab chalta hun

to hi 'ab' kal banta hai

jiske aasman mein smritiyan

bijli bankar kaundh ti hein

aur tumahri kalam ki syaahi mai tabdeel ho jaati hai

Wo chalta gaya

aur mein bhi mudkar chalne laga

duur nikal aaya

aur phir bijli kaundh ne lagi

aur meri kalam chalne...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)