It is virtually the last milestone of prosperity, also marking the end of Gurgaon. As young software techie couples, wearing Nike sneakers and Levis Jeans step out of their Hondas to have a lazy brunch at the Haldiram’s, you almost forget that you are in India. Before this point, there are 24-hours power-backed apartments. Cheerleading

Thomas Friedman are boys who turn from Pawan to Peter during the night.

I am travelling on the Golden Quadrilateral, one of the last symbols of the Vajpayee Government. Till few years ago, huge pictures of the former Prime Minister would don toll plazas built at various spots on the super highway. The pictures are gone but you can still find traces of the NDA era. At such one place on the National Highway 8, I meet Rajpal.

Outside the ‘

Feel Good’ wine shop, Rajpal is quietly gulping down Old Monk mixed with Pepsi at 11 am. Our eyes meet and I strike a conversation with him. After a few minutes of polite conversation, he finally opens up, helped partially by the good old rum. He looks at me, points at the bottle and says, “ This is just to ward off loneliness. Have you heard this song: I feel so lonely baby, I feel so lonely, I could die…?” Though I am not fond of Elvis Presley, I recognize this song. Before I can utter a word, he continues.

“As a young man, I was inspired by Manoj Kumar’s

Upkaar. I joined the Army. But in a few years time, I was disillusioned. I quit and returned to my village. I became a farmer, tilling my father’s land. But that also did not hold me for long. It is a cycle of

Karma.”

“What do you do now?,” I ask him. He looks at me and smiles. “I just feel good now,” he mutters, followed by a hearty laugh. As I take out my camera to click a picture, he refuses to be photographed. “OK, but at least tell me where did you hear Elvis Presley?,” I ask him.

“In the Army, I was attached with a Colonel. He was very fond of old songs. Every evening he would play this song on his gramaphone and sing along with it. I picked it from there,” he says. We shake hands. “See me again while you are coming back; just ask this shopkeeper and he will guide you,” he adds.

I move on. Just before Kotputli, on the Jaipur highway, I enter a field where a turbaned man is sitting on the earth, a flute resting beside him. There are goats grazing nearby. His back is turned against me and so he is almost startled as I greet him. I tell him I have come from Delhi and would like to ask him few questions. His name is Raja Ram and he is 60 years old. He has been a farmer all his life. He has never been to Delhi or Jaipur. He lives nearby and has no electricity in his house. He has never heard of Sachin Tendulkar. “Who is Abdul Kalam?,” I ask him. “He was a fakir,” he replies. “What is your wish list for 2007?” He looks at me as I put this question to him and then looks at his goats. “Nothing,” he replies.

Just before Jaipur, around 240 kilometres from Delhi, I spot Reema, a young college girl, waiting for a bus on the highway. I cautiously approach her lest other men at the bus-stop might think I am teasing her. I introduce myself and tell her about my assignment. I can see that few boys at the bus-stop are looking at us with curiosity. One of them passes a comment, making others laugh. I can hear them talking about ‘jeans.’ I notice that Reema is wearing jeans. Reema begins telling me about her family. Her father is a farmer and after much persuasion she was allowed to study further in a college. “Usually girls of my age are married off but I managed to wriggle out of it, at least for now,” she says. She wants to become a teacher. And what are her expectations from 2007? She looks at the jeering boys and says,“ I wish I could wear jeans without inviting comments from them.”

Further ahead, I meet Ratan Lal, a young boy, who studies in 8th class in a government school. His village, Chapakhedi is a few kilometers away from the highway, which goes on to Mumbai. He wants to join Army when he grows up. Has he ever seen a computer? “No,” he replies almost apologetically, “but I have heard about it,” he asserts. “What is it?” “It is an electronic pigeon, used for sending messages,” he answers. What does he want in 2007? “I wish I could see a cricket match on television,” he says.

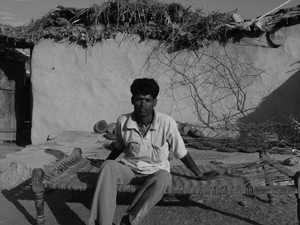

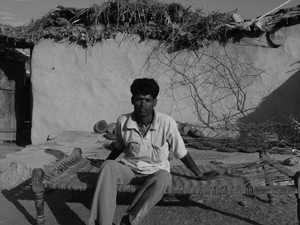

Along the National Highway, in Rajasthan’s Chittorgarh district, I meet Kishan Lal, 24, who drives a taxi. He is a lower caste. “ Come, I will take you to my village,” he says. His village Achalpura is situated along the highway. “This highway came up a few years ago but, you see, it brought no changes in our lives,” he tells me. Till a year ago, Kishan Lal says, the people of his community could not sit on a cot in his village.

“The upper caste men would object to this, maintaining that we had no right to sit on a cot,” he says. Last year, some of the boys of his caste, along with a few social activists began a ‘khaat andolan.’ They would take out cots from their houses and sit on them outside. Some of them were beaten up by drunken upper caste men. “They also declared a social boycott against us,” remembers Ram Lal. But still, he says, only 50 percent lower castes are with them. “The rest of them still prefer a non-confrontationist approach,” he says as he sits on a cot outside his house for a photo op.

A few kilometers before Udaipur is Idra gram panchayat, where 50 gypsy families have built small settlements. “We were tired of always being on the move and decided to settle here for the sake of the new generation,” says Banjara leader Bansilal. He laments that no politician pays heed to them since most of them do not vote. “We are always on the move, searching for jobs. If someone is working in Gujarat, how is he supposed to spend 500 rupees and come here for voting?,” he says. What is his expectation from 2007? “The Police harass us a lot here. I wish that could change,” Bansilal says, urging me to have a cup of tea at his house.

On my way back, I am reminded of my promise made to Rajpal. As the evening descends, I reach the spot where I had left him two days back. The shutter of the Feel Good wine shop is half open and in the dim light, I ask the owner about Rajpal. “He is holding his Panchayat behind this shop, in the fields. There is a turn there, you can go inside,” he says with an amused look on his face. And true to his words, I find Rajpal with his bottle, surrounded by a few men. He is regaling them with his stories.

“Oh here comes the babu,” he shouts as his eyes fall on me. I can sense that he has had a little too much. “Ok, let me play

Kaun Banega Crorepati with you,” he says, and without waiting, he throws a question at me, increasing the baritone of his voice to match with that of Amitabh Bachchan, “Why is this country infested with so many problems?” I can feel all eyes set upon me. Before I can gather an answer, Rajpal comes to my rescue. “I think you need a phone-a-friend helpline,” he says, shifting from one foot to another. It is absolute dark as I hear his voice sifting through the air:

Hello Manmohan Singh ji, mein Amitabh Bachchan bol raha hun…

(This report appeared in the New Year special issue of

The Sunday Indian)